Doctors Blogs by The Center for Occupational and Environmental Medicine in Charleston, SC

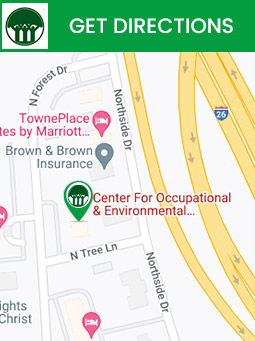

Our blog features health topics that matter to you. Visit The Center for Occupational and Environmental Medicine (COEM) today to get specialized care. For more information, contact us today or schedule an appointment online. We are conveniently located at 7510 North Forest Drive North Charleston, SC 29420.

Adventures in Allergy testing at COEM

Substitute chocolate, pizza, or any other food people love, and you have a comment we hear all the time when patients are being tested for foods.

Understanding Detox

‘Detox’ is the short form of the word detoxification, a process by which our bodies break down and get rid of toxic substances. It is another important system of the body.

Depression

The worst illness we could suffer from is depression. It is overwhelming in its devastation. The guilt, shame, and paralysis are unseen and unable to be adequately explained or understood.

Environmental Toxins

Environmental toxins are harmful substances that can adversely affect your health. They are composed of poisonous chemical compounds and organisms that cause various diseases.

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is an infectious liver disease. It is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). Infections of hepatitis B occur only if the virus is able to enter the blood stream and reach the liver.

Food Allergy

Food Allergy is an abnormal response to a particular food, triggered by the body’s immune system. The immune system is responsible for identifying and destroying the invaders like bacteria and viruses of our body that can make us sick.

Autism & Children with Special Needs

At the Center for Occupational and Environmental Medicine, we believe that it is inadequate to simply give children drugs for developmental disorders without evaluating and correcting underlying problems.

Healthy for Life Weight Loss

As a medical practice, it is in our best interest, too, if you succeed. As your weight normalizes and the very real and severe medical risks caused by obesity are diminished, our ability to help you in other ways with your health is facilitated.

Lyme Disease: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment

Lyme disease (LD) is an infection caused by Borrelia Burgdorferi, a type of bacterium called a spirochete that is carried by deer ticks. An infected tick can transmit the spirochete to the humans and animals it bites.

Yeast Eradication

Establishing and nourishing the growth of beneficial bacteria in our digestive tracts is one of the most misunderstood and neglected things we can do to regain and maintain our health.

Menopause: Symptoms, Causes, Treatment and BHRT Connection

Menopause is the point in a woman’s life when her menstrual cycles come to an end. It’s often diagnosed after 12 months of not having a menstrual cycle and not being pregnant.

Swine Flu (H1N1) Could Reach 40 % in U.S.

The wording of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) was ominous – “In a disturbing new projection, health officials say up to 40 percent of Americans could get swine flu this year and several hundred thousand could die without a successful vaccine campaign and other measures.”

What is Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy? Know the Facts and Risks

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy involves breathing pure oxygen to treat various medical conditions and wounds inside a special room or chamber.

Can Hypothyroidism Cause Depression?

Can hypothyroidism cause depression and anxiety? Well, depression can often be a symptom of hypothyroidism. However, only a specialist can diagnose if your depression is caused due to hypothyroidism.

How to Manage Allergies in Spring Season?

Whenever your immune system responds to an unfamiliar substance that doesn’t cause a reaction in most people, referred to as an allergen, you have an allergy.

Esophagitis: Types, Common Symptoms, Causes, and Treatment Options

Esophagitis is an inflammation that may damage the tissues of the esophagus. It makes it difficult to swallow food and can be caused by infection, allergies, oral medications, etc.

Allergy and Asthma: How Are They Connected?

Many types of allergies can cause asthma in people with inflamed and sensitive airways. However, asthma triggers vary from person to person.

Bioidentical Hormone Replacement Therapy: Everything You Need to Know

Hormones are specific chemicals produced by various glands in our bodies that control most of our daily functions.

Pandas Syndrome: What to Know About It

PANDAS is an acronym for pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric diseases associated with streptococcus. Following infection with Streptococcus pyogenes, children experience abrupt and typically substantial changes in personality, behavior, and mobility.

What Should You Keep in Mind While Doing Yoga with Scoliosis

Scoliosis is characterized by an abnormal sideways curvature of the spine, often diagnosed in childhood and early adolescence. While moderate and severe scoliosis requires medical intervention, mild scoliosis can be effectively managed by yourself, such as with yoga.

Vitamin D and Inflammation: How It Can Affect Your Health

Vitamin D, in addition to its important role in calcium homeostasis, has recently been discovered to play a role in immune and inflammation system modulation.

Inflammatory Bowel Disorder (IBD) and Food Sensitivities: Know the Connection

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an umbrella term for conditions characterized by chronic inflammation of the digestive system.

Mold and Dampness: How Mold Affects Your Health

Mold is a form of fungus composed of microscopic organisms found practically everywhere. Molds perform a crucial function in nature by decomposing dead leaves, plants, and trees.

Mold and Cancer: Can Mold Cause Cancer?

Indoor exposure to black mold, or any other mold, has not been linked to cancer. However, mold is linked to various other health issues.

Mycotoxins Toxicity: What You Need to Know

Mycotoxin toxicity is a poisoning caused by mycotoxins found in mold (fungi) that grow on food like cereals, dry fruits, and coffee beans when left exposed to air for a long time.

Osteoporosis: Symptoms, Causes, Prevention and Treatment

Osteoporosis, also known as ‘porous bone’, is a disease in which bones get so brittle that they get fractured easily with the slightest stress or a fall. This disease occurs due to low bone mass and less bone turnover.

Preconception Care and Fertility: Everything You Need to Know

Preconception care is personalized care given to women and men that reduces maternal and fetal mortality and morbidity—the likelihood of conception increases when parents are provided contraceptive counseling.

The Hidden Connection Between Eczema and Gut Health

Eczema is a condition in which patches of skin become inflamed, itchy, cracked, rough, and sometimes even cause blisters. Scientists are now slowly understanding the role of the human microbiome in the appearance of chronic conditions like eczema.

Can Exposure to Mold Cause Miscarriage and Birth Defects During Pregnancy?

Mold is a living organism that belongs to the domain of Fungi. Fungi are unique in that they appear plant-like, but they are neither plant nor animal.

What are the Main Benefits of Lifestyle Medicine?

Medicine has existed for as long as humans have been diseased. Some healing techniques have been utilized worldwide among various cultures and diverse groups to restore their health.

Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO): Everything You Need to Know About It

Small intestine bacterial overgrowth is more likely to affect women, older persons, and those who have other digestive problems, such as Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS).

Can You Treat Allergies Using Natural Antihistamines?

Antihistamines are a group of medications used to treat allergy symptoms. These medications aid in treating unpleasant symptoms caused by the presence of an excess of histamine, a substance produced by your body’s immune system.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) – All You Need to Know

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is a hormonal disorder that affects women and can cause chronic health problems like heart disease or type 2 diabetes. However, early diagnosis and treatment can reduce your risk of developing those complications.

Probiotics and Prebiotics: The Best Foods You Should Eat

Probiotic foods naturally contain useful bacteria. Several readily available foods, like yogurt, naturally contain beneficial bacteria.

Connection Between Gut Bacteria and Heart Disease: Best Probiotics for Gut Health

Probiotics are live microbes that provide great health benefits. Some evidence suggests that certain types can reduce cholesterol, blood pressure, and inflammation.

Medical Myths Associated with Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is a chronic medical condition that affects the spinal cord and brain. Experts mostly believe that MS is an autoimmune disease. In this disease, the immune system attacks the protective sheath that covers nerve fibers, known as myelin.

Alpha Lipoic Acid: A Universal Anti-oxidant

Alpha Lipoic Acid is an anti-oxidant, which works like other more familiar anti-oxidants such as Vitamins E and C.

Multiple Sclerosis And The Immune System How Are They Connected

Multiple Sclerosis is a potentially incapacitating disease of the spinal cord (central nervous system)and brain. In this condition, a person’s immune system attacks the myelin (a protective sheath) that covers the nerve fibers.

What Is the Functional Medicine Approach to Weight Loss And Obesity

The first thing to analyze is why you cannot keep your weight off. Once this is understood, you need to work with your functional medicine doctor to select the most appropriate treatment plan for you.

Autoimmune Diseases and Toxic Chemical Exposure: Is There a Connection?

Our daily environment presents many toxic chemicals that can affect the hormones in our bodies. Since most autoimmune diseases are linked to our various hormones, most scientists believe that toxic chemicals may also trigger autoimmune diseases.

Understanding Hypothyroidism from a Functional Medicine Perspective

Functional hypothyroidism also referred to as subclinical hypothyroidism, is a state where thyroid hormone levels within your blood fall within the normal range. However, other indicators such as temperature tests show mild thyroid hormone deficiency.

Gut Microbiome and Mental Health: Impact of Gut Microbiome On Your Mental Health

A gut microbiome is a group of trillions of bacterial cells found mainly in your colon. Your colon is responsible for absorbing nutrients into the body and is also directly connected to the brain.

Mold and Asthma – What’s the Connection and its Effects on Your Health

When exposed to mold, people with asthma suffer from shortness of breath and overall reduced lung function. When mold is inhaled, their airways produce more mucus, may constrict, and become swollen.

Preventing And Treating Cancers: You Do Have Choices

Over the course of the past several weeks I have learned of the untimely death of a few of my patients and family members. What was so tragic was these people were given no information about alternative treatments that might have provided some hope.

How to Remove Mold Spores From Your House And Prevent Mold Infection?

Mold is extremely common as it grows in damp places, such as roofs, windows, pipes, or any previously flooded area.

Role of Food Sensitivities in Asthma and Inflammatory Bowel Disorders

Michael Radcliff and other speakers emphasized the importance of food in unexplained illness. 50-60% of brittle asthmatics will improve when their food sensitivities are addressed.

Food Intolerance: Everything You Should Know About It

Typically when someone reacts to a particular food, that person has a food intolerance rather than a true allergy to that food. Despite their similar symptoms, a food allergy can be more critical.

Hypothyroidism vs. Hyperthyroidism: What’s the Difference?

Thyroid hormone is critical for the proper functioning of almost every tissue in the body. Thyroid hormone affects heart rate, body temperature, body weight, and cholesterol metabolism.

Food Allergies: Things You Must Know

Food allergies are the immune system’s reaction to certain foods, triggering symptoms that can affect different parts of the body.

Mold Mycotoxins: Important Things You Should know

There are many types of brain injuries. These may occur as a result of blows to the head, gunshot wounds, accidents, strokes, sports injuries, electrical and lightning injuries, migraine headaches, vascular problems, degenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis, and from normal pressure hydrocephalus.

Mold Assessment: What You Should Know About It

We should be able to enjoy living near coastal areas without fear of mold issues. Proper assessment and care of indoor environments makes all the difference!

A Challenging Case History of Vertigo at The Center

She was a cosmetologist working in a mall. One day she bought a raffle ticket for a charity and was pleasantly surprised when she learned that she had won a free cruise to the Bahamas.

Chronic Fatigue Immune Dysfunction Syndrome: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment

Chronic fatigue syndrome, Chronic Fatigue Immune Dysfunction Syndrome (CFIDS), or CFS is a complex disorder indicated by extreme fatigue that usually worsens with any activity, be it mental or physical, and does not improve with rest.

Mold Exposure Health Risks: Can Mold Make You Sick?

Mold is a fungus that develops on humid or damp spots such as ventilation ducts, walls, shower cubicles, bathrooms, etc.

Do You Know What Makes Functional Medicine Different?

Functional medicine is a patient-centered, individualized, and science-based approach that allows practitioners and patients to work together and promote optimal wellness by addressing the underlying causes.

Why Do I Keep Getting Yeast Infections?

A vaginal yeast infection, also known as candidiasis, is a fungal infection. When the balance of bacteria and yeast cells in the vagina changes, the yeast cells can multiply and cause an infection.

Fatty Liver Disease: All You Need to Know

Fatty liver disease, otherwise known as hepatic steatosis, is the condition in which fat accumulates in the liver. Having fat in your liver is normal, however, having too much fat in your liver can cause liver inflammation and scarring.

Progesterone – One Heck of a Hormone

Progesterone gets its name from “for gestation” because its highest levels occur during pregnancy. Without the high levels a mother would reject her boy baby.

Overview of Candida Albicans

The Yeast Connection brought down the wrath of conventional medicine upon us for treating our patients with anti-fungal medications. We had at the time only Nystatin, one of the safest drugs in the whole Physicians Desk Reference.

Yeast-Yet Again! (An Interview with Dr. Lieberman)

Dr. Lieberman: When I first started working in this field in the late 1970’s, I thought every patient had yeast, and I treated everybody accordingly.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Conference

This meeting was a breath of fresh air as leaders were chosen for their ability to present new and old, yet more unaccepted, ideas on the causes of this ever-growing problem seen in children.

Latex Sensitivity: Facts You Should Know About It

There is a growing concern over latex sensitivity. Latex is very strongly allergenic and is nearly everywhere.

Biochemical Abnormalities of Autism

The biochemical abnormalities of autism were brilliantly presented by Rosemary Waring.

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Toxic Chemical Exposure

Dr. Dunstan of Australia presented an interesting paper on the relationship of toxic chemical exposures to infection – specifically asking if toxicity was related to CFIDS (Chronic Fatigue Immune Dysfunction Syndrome).

Fibromyalgia Fatigue and Chronic Fatigue

Fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome are disorders characterized by extreme fatigue. The medical community debates whether fibromyalgia is a different expression of the same disease that causes chronic fatigue syndrome as the conditions are intertwined.

Mercury Toxicity

Mercury is a toxic heavy metal that is widespread in nature. Most mercury exposure to humans is due to the ingestion of contaminated fish, the release of mercury from dental amalgam, or occupational exposure.

Chlorine Poisoning

Chlorine poisoning is a medical emergency which occurs upon inhaling or swallowing chlorine. If a person is showing symptoms of poisoning, they should be immediately taken to the hospital or emergency room.

Low Level Carbon Monoxide Poisoning

One of the most common symptoms of chronic low level carbon monoxide exposure is severe muscle pain or a flu like illness associated with memory loss, headaches, and dizziness.

Organophosphate Pesticide Exposure

Dr. Goran Jamal of Glasgow presented a most important paper on Organophosphate pesticide exposure.

Endocrine (Hormonal) System

Dr. Lieberman’s Note: We are sorry to see that people generally have so little understanding of the adverse effects of using so many toxic chemicals in their daily lives and that they are equally unaware of effective, safer alternatives.

Chemical Toxicity and Biologic Exposures

Related to the above paper, the Nicholsons presented their research on Gulf War illnesses. They believe that chemical toxicity and biologic exposures combined to produce these illnesses. It has now been documented that both chemical and biological warfare were used in the Gulf War.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Everything You Need to Know

ADHD is characterized by the continuous display of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity that restricts brain development. This disorder mainly affects children and teens and in some cases, continues into adulthood as well.

Carbon Monoxide Poisoning & Its Association With Fatigue And Fibromyalgia

Carbon monoxide poisoning is a life-threatening condition caused by exposure to high levels of Carbon monoxide, also known as CO. CO poisoning, one of the most common fatal poisonings, occurs by inhalation.